- Home

- H. G. Wells

In the Days of the Comet Page 21

In the Days of the Comet Read online

Page 21

Section 1

FROM that moment when I insulted old Mrs. Verrall I becamerepresentative, I was a man who stood for all the disinherited ofthe world. I had no hope of pride or pleasure left in me, I wasraging rebellion against God and mankind. There were no more vagueintentions swaying me this way and that; I was perfectly clear nowupon what I meant to do. I would make my protest and die.

I would make my protest and die. I was going to kill Nettie--Nettiewho had smiled and promised and given herself to another, and whostood now for all the conceivable delightfulnesses, the lost imaginationsof the youthful heart, the unattainable joys in life; and Verrallwho stood for all who profited by the incurable injustice of oursocial order. I would kill them both. And that being done I wouldblow my brains out and see what vengeance followed my blank refusalto live.

So indeed I was resolved. I raged monstrously. And above me,abolishing the stars, triumphant over the yellow waning moon thatfollowed it below, the giant meteor towered up towards the zenith.

"Let me only kill!" I cried. "Let me only kill!"

So I shouted in my frenzy. I was in a fever that defied hungerand fatigue; for a long time I had prowled over the heath towardsLowchester talking to myself, and now that night had fully come Iwas tramping homeward, walking the long seventeen miles without athought of rest. And I had eaten nothing since the morning.

I suppose I must count myself mad, but I can recall my ravings.

There were times when I walked weeping through that brightness thatwas neither night nor day. There were times when I reasoned in atopsy-turvy fashion with what I called the Spirit of All Things.But always I spoke to that white glory in the sky.

"Why am I here only to suffer ignominies?" I asked. "Why have youmade me with pride that cannot be satisfied, with desires thatturn and rend me? Is it a jest, this world--a joke you play on yourguests? I--even I--have a better humor than that!"

"Why not learn from me a certain decency of mercy? Why not undo?Have I ever tormented--day by day, some wretched worm--makingfilth for it to trail through, filth that disgusts it, starving it,bruising it, mocking it? Why should you? Your jokes are clumsy.Try--try some milder fun up there; do you hear? Something thatdoesn't hurt so infernally."

"You say this is your purpose--your purpose with me. You are makingsomething with me--birth pangs of a soul. Ah! How can I believeyou? You forget I have eyes for other things. Let my own case go,but what of that frog beneath the cart-wheel, God?--and the birdthe cat had torn?"

And after such blasphemies I would fling out a ridiculous littledebating society hand. "Answer me that!"

A week ago it had been moonlight, white and black and hard acrossthe spaces of the park, but now the light was livid and full ofthe quality of haze. An extraordinarily low white mist, not threefeet above the ground, drifted broodingly across the grass, andthe trees rose ghostly out of that phantom sea. Great and shadowyand strange was the world that night, no one seemed abroad; I and mylittle cracked voice drifted solitary through the silent mysteries.Sometimes I argued as I have told, sometimes I tumbled along inmoody vacuity, sometimes my torment was vivid and acute.

Abruptly out of apathy would come a boiling paroxysm of fury, whenI thought of Nettie mocking me and laughing, and of her and Verrallclasped in one another's arms.

"I will not have it so!" I screamed. "I will not have it so!"

And in one of these raving fits I drew my revolver from my pocketand fired into the quiet night. Three times I fired it.

The bullets tore through the air, the startled trees told one anotherin diminishing echoes the thing I had done, and then, with a slowfinality, the vast and patient night healed again to calm. My shots,my curses and blasphemies, my prayers--for anon I prayed--thatSilence took them all.

It was--how can I express it?--a stifled outcry tranquilized,lost, amid the serene assumptions, the overwhelming empire of thatbrightness. The noise of my shots, the impact upon things, hadfor the instant been enormous, then it had passed away. I foundmyself standing with the revolver held up, astonished, my emotionspenetrated by something I could not understand. Then I looked upover my shoulder at the great star, and remained staring at it.

"Who are YOU?" I said at last.

I was like a man in a solitary desert who has suddenly heard a voice. . . .

That, too, passed.

As I came over Clayton Crest I recalled that I missed the multitudethat now night after night walked out to stare at the comet, andthe little preacher in the waste beyond the hoardings, who warnedsinners to repent before the Judgment, was not in his usual place.

It was long past midnight, and every one had gone home. But I didnot think of this at first, and the solitude perplexed me and lefta memory behind. The gas-lamps were all extinguished because of thebrightness of the comet, and that too was unfamiliar. The littlenewsagent in the still High Street had shut up and gone to bed,but one belated board had been put out late and forgotten, and itstill bore its placard.

The word upon it--there was but one word upon it in staringletters--was: "WAR."

You figure that empty mean street, emptily echoing to my footsteps--nosoul awake and audible but me. Then my halt at the placard. Andamidst that sleeping stillness, smeared hastily upon the board,a little askew and crumpled, but quite distinct beneath that coolmeteoric glare, preposterous and appalling, the measureless evilof that word--

"WAR!"

Ann Veronica: A Modern Love Story

Ann Veronica: A Modern Love Story The Time Machine

The Time Machine The First Men in the Moon

The First Men in the Moon The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents

The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents The War of the Worlds

The War of the Worlds The Invisible Man: A Grotesque Romance

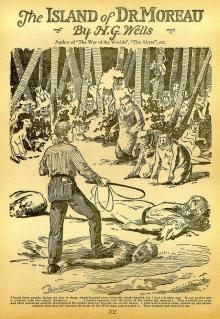

The Invisible Man: A Grotesque Romance The Island of Doctor Moreau

The Island of Doctor Moreau The Door in the Wall, and Other Stories

The Door in the Wall, and Other Stories The Best Science Fiction Stories of H G Wells

The Best Science Fiction Stories of H G Wells The Sea Lady

The Sea Lady The Wonderful Visit

The Wonderful Visit Love and Mr. Lewisham

Love and Mr. Lewisham Marriage

Marriage Tales of Space and Time

Tales of Space and Time The War of the Worlds (Penguin Classics)

The War of the Worlds (Penguin Classics) Twelve Stories and a Dream

Twelve Stories and a Dream The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth

The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth Tono-Bungay

Tono-Bungay The War in the Air

The War in the Air The Sleeper Awakes

The Sleeper Awakes The Country of the Blind and Other Stories

The Country of the Blind and Other Stories Kipps

Kipps The World Set Free

The World Set Free The Country of the Blind and other Selected Stories

The Country of the Blind and other Selected Stories Ann Veronica

Ann Veronica Ann Veronica a Modern Love Story

Ann Veronica a Modern Love Story The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds

The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds Time Machine and The Invisible Man (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Time Machine and The Invisible Man (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Time Machine and The Invisible Man

The Time Machine and The Invisible Man The Island of Dr. Moreau

The Island of Dr. Moreau Selected Stories of H. G. Wells

Selected Stories of H. G. Wells Island of Dr. Moreau

Island of Dr. Moreau THE NEW MACHIAVELLI

THE NEW MACHIAVELLI