- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Ann Veronica: A Modern Love Story

Ann Veronica: A Modern Love Story The Time Machine

The Time Machine The First Men in the Moon

The First Men in the Moon The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents

The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents The War of the Worlds

The War of the Worlds The Invisible Man: A Grotesque Romance

The Invisible Man: A Grotesque Romance The Island of Doctor Moreau

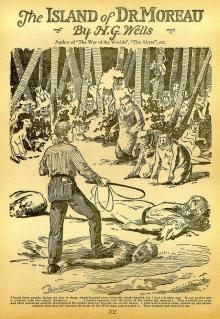

The Island of Doctor Moreau The Door in the Wall, and Other Stories

The Door in the Wall, and Other Stories The Best Science Fiction Stories of H G Wells

The Best Science Fiction Stories of H G Wells The Sea Lady

The Sea Lady The Wonderful Visit

The Wonderful Visit Love and Mr. Lewisham

Love and Mr. Lewisham Marriage

Marriage Tales of Space and Time

Tales of Space and Time The War of the Worlds (Penguin Classics)

The War of the Worlds (Penguin Classics) Twelve Stories and a Dream

Twelve Stories and a Dream The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth

The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth Tono-Bungay

Tono-Bungay The War in the Air

The War in the Air The Sleeper Awakes

The Sleeper Awakes The Country of the Blind and Other Stories

The Country of the Blind and Other Stories Kipps

Kipps The World Set Free

The World Set Free The Country of the Blind and other Selected Stories

The Country of the Blind and other Selected Stories Ann Veronica

Ann Veronica Ann Veronica a Modern Love Story

Ann Veronica a Modern Love Story The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds

The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds Time Machine and The Invisible Man (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Time Machine and The Invisible Man (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Time Machine and The Invisible Man

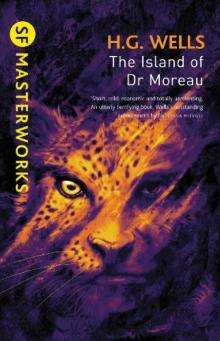

The Time Machine and The Invisible Man The Island of Dr. Moreau

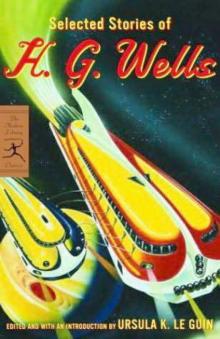

The Island of Dr. Moreau Selected Stories of H. G. Wells

Selected Stories of H. G. Wells Island of Dr. Moreau

Island of Dr. Moreau THE NEW MACHIAVELLI

THE NEW MACHIAVELLI